The High Cost of Geographically Illiterate Economists

April 23, 2014

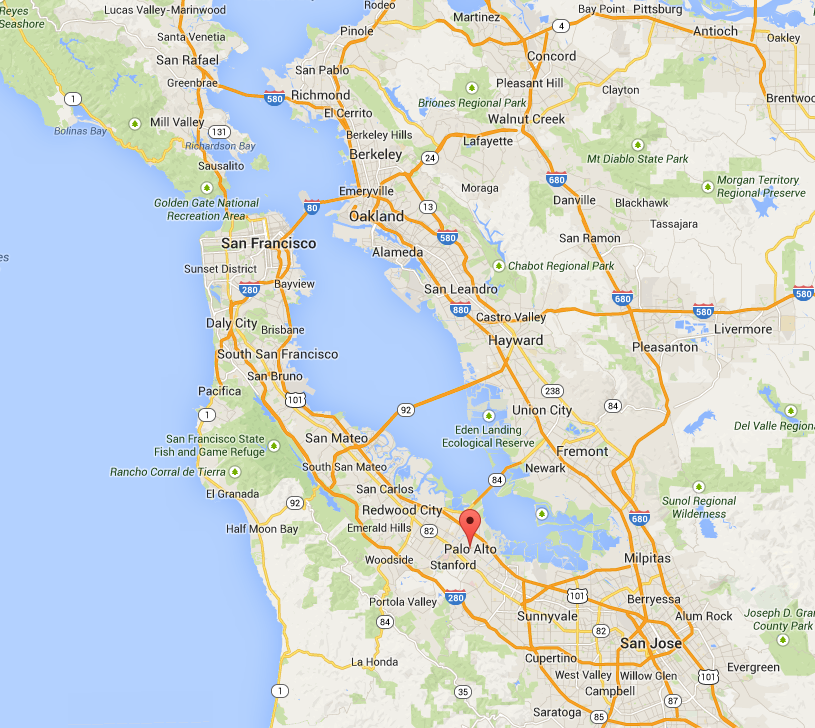

Today I read an article written by economist and columnist Thomas Sowell. The piece is entitled “The High Cost of Liberalism“. The article uses the example of extraordinarily high single family housing prices in Palo Alto, California as an attempt to argue that “liberal” policies don’t work. His thesis seems to be that a desire for allocation of green space is just one of many liberal governing practices that lead to high prices. His implication of course is that “liberalism” is bad not just for real estate prices but for everything else as well. I think it might be time for him to buy a map.

I love when economists talk about real estate but omit any and all geographical context as if location, at various spatial scales, is irrelevant. Haven’t they heard the “location, location, location” real estate mantra? Here’s what Dr. Sowell says about the abundance of land near Palo Alto:

“There are people who claim that astronomical housing prices in places like Palo Alto and San Francisco are due to a scarcity of land. But there is enough vacant land (“open space”) on the other side of the 280 Freeway that goes past Palo Alto to build another Palo Alto or two — except for laws and policies that make that impossible.”

Isn’t it great the way he refers to the land west of the 280 Freeway as “vacant” and “open space”? Just a huge collection of vacant lots with wells ready to pump water and utilities ready to hook up to cookie-cutter housing developments, right? If only those darn liberals would give everyone permission to build legions of condos, all of the SF Bay area would suddenly be affordable.

In the naive world of neoclassical economists who can’t be bothered with geographical data elements or other real world constraints, he’s correct; the area west of the 280 is sparsely populated. What he glosses over, however, is typical of the army of geographically illiterate economists who seem to feel entitled to dictate policy without actually understanding anything about the physical world. Trivial details regarding water resources, topography, natural hazards, transportation infrastructure, etc don’t really matter to most economists because they can calculate elasticity of demand and that’s good enough … at least for their fellow economists. If you’re a geographer you have to push well beyond supply and demand and sort through layer after layer of physical and cultural geography to properly understand a region before you divide it up and hand out building permits.

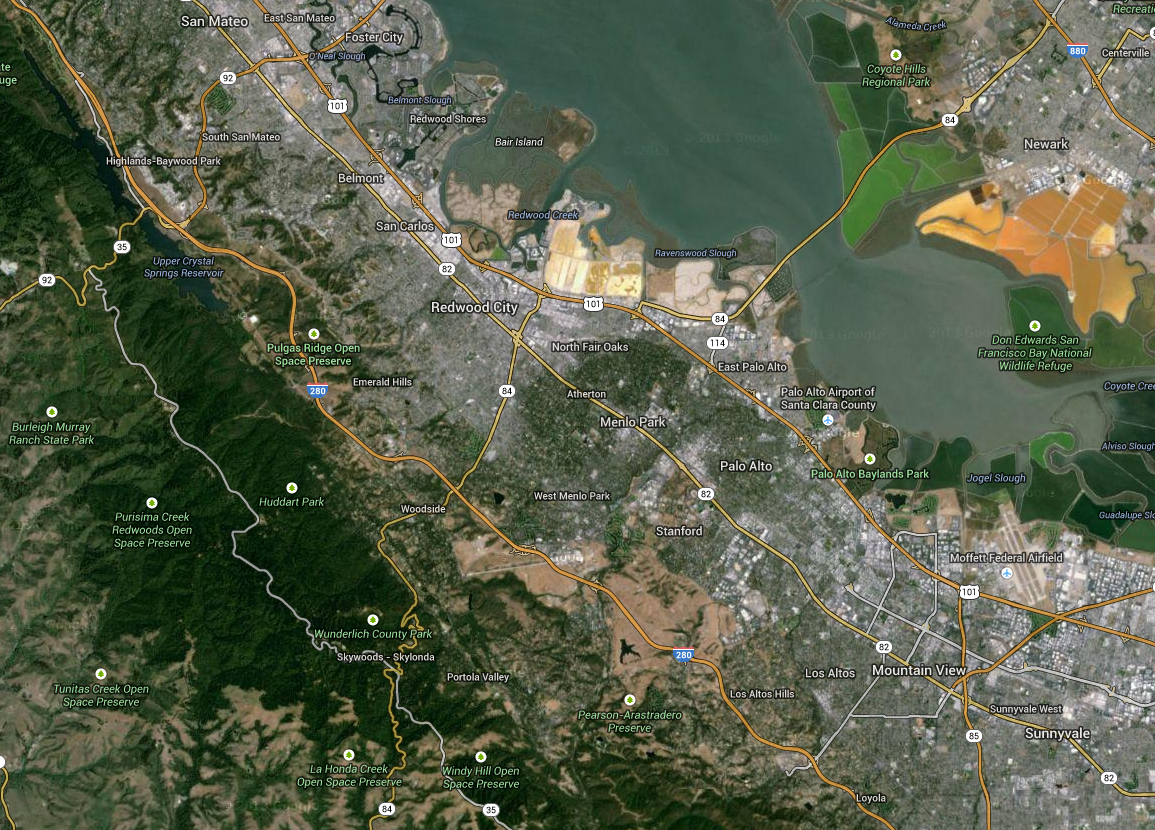

The western half of the San Francisco Peninsula has varied topography climbing from sea level on the Pacific Coast up to about 2,500 to 3,500 feet (750-1,000 meters) at some peaks in the northern part of the Santa Cruz Mountains and then back down to near sea level in the heavily populated strip of land next to the San Francisco Bay, known to most people as Silicon Valley. So Dr. Sowell’s prime building area is mountainous. It’s also a biologically diverse area with an equally diverse range of climatic conditions. Most of the area is classified as temperate rainforest but there are areas of dry chaparral and coastal old growth forest, to name a couple. The region is a groovy place to build a cabin tucked in the woods, and I think the Woodside – Portola Valley area does indeed have low density residential properties that fit the bill (except they’re probably the 3,000 sq ft variety complete with steel appliances, granite counter tops, cherry cabinets and heated tile floors … plus, of course, a heated garage for the Tesla). But the region west of 280 is not setup for “another Palo Alto or two” for a few glaring reasons.

We’ll call these the “Ask Any Geographer” (AAG) set of reasons not to open the area for residential development. Here are four such reasons that would appear near the top of the list.

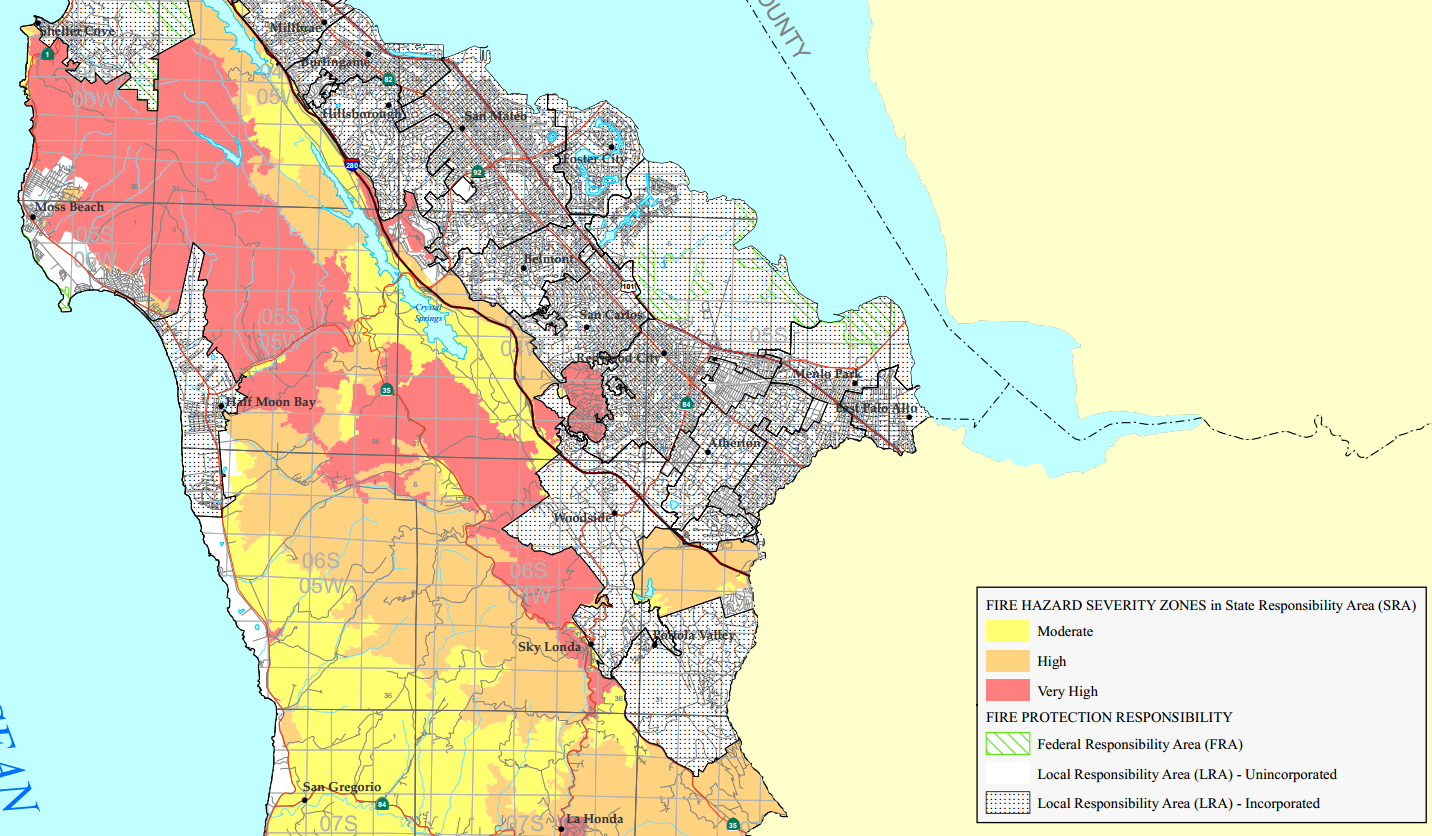

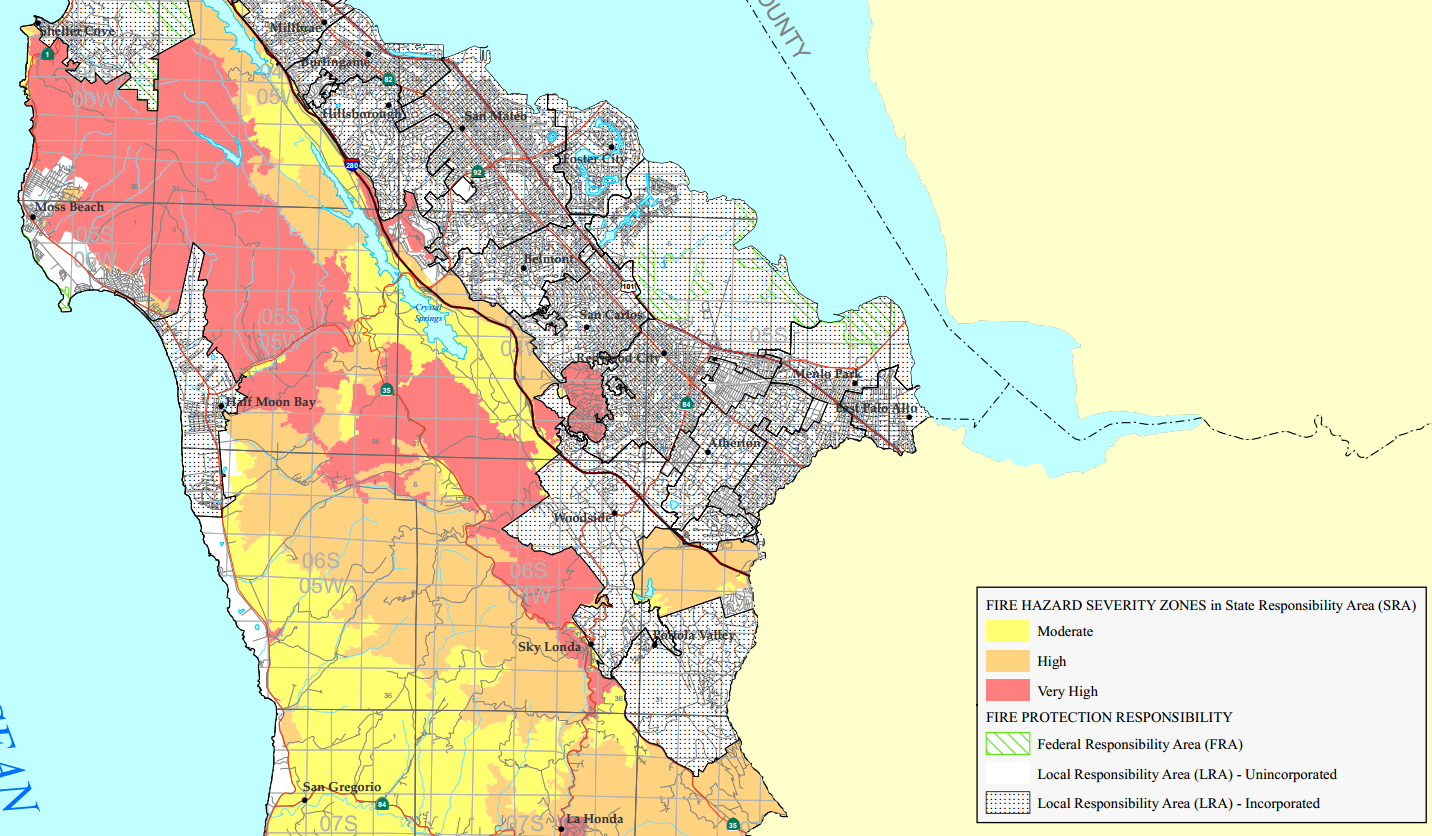

AAG Reason #1: Wildfires. In my home state of Colorado over 1 Million people reside in areas deemed high risk for wildfire and the cost of protecting property owners from the inevitable wildfire activity in such regions is far too high. Isn’t it funny how fiscal conservatives hate high taxes and want less government but don’t bother to think about downstream risks inherent with build anywhere and everywhere regional planning policies? The mountainous and forested region west of I-280 is a region where wildfires will occur. The question is not if but when. Hey Thomas, how would the supply and demand equation change if New Palo Alto was built, sold and settled but then burned down? Good for the local economy? Real estate and otherwise? Something tells me your “econ 1” model falls apart in such a scenario.

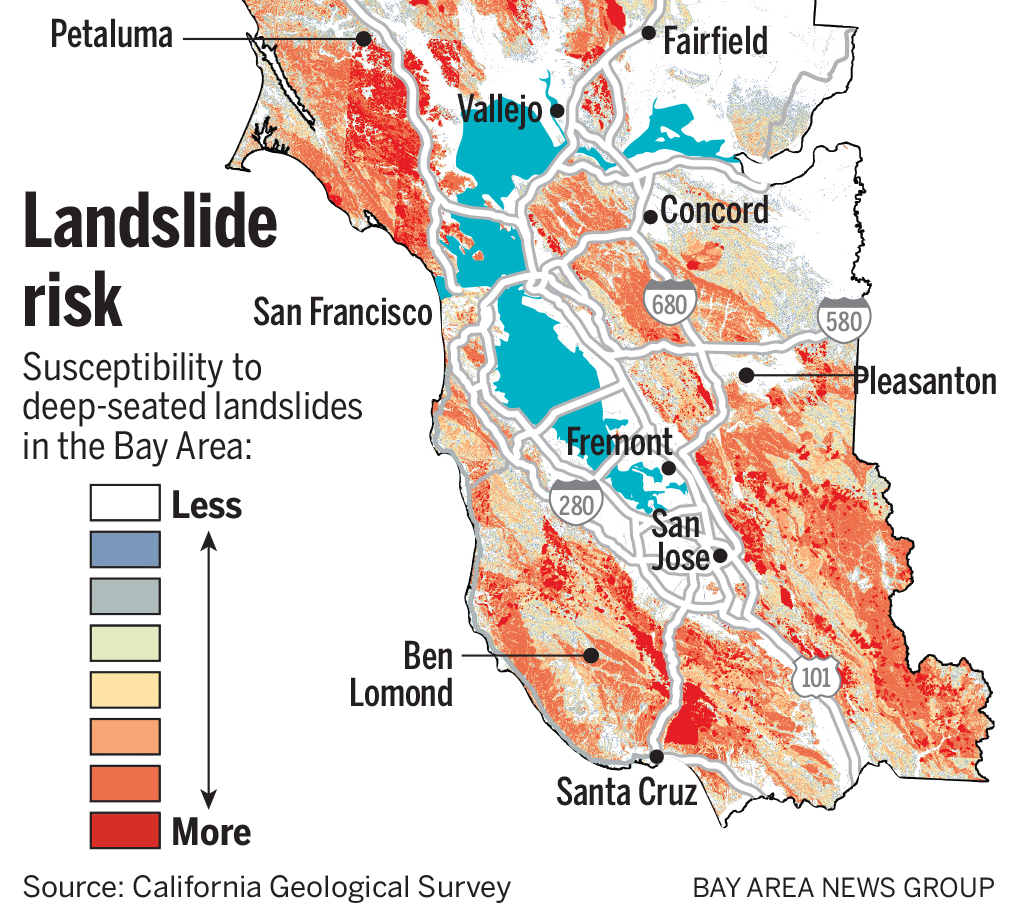

AAG Reason #2: Landslides. As I mentioned above, this region is mostly temperate rainforest. For Dr. Sowell and other economists who might be reading, this means it rains a lot and it’s covered with trees. One of a few potential hazards that occur frequently after heavy rains in mountainous, forested regions are landslides. They can be small and relatively inconsequential or they can be much bigger threatening homes and communities and resulting in fatalities. Recently there were major landslides in the Seattle, Washington area killing more than 40 people, and the area west of Palo Alto is subject to landslide risk as well.

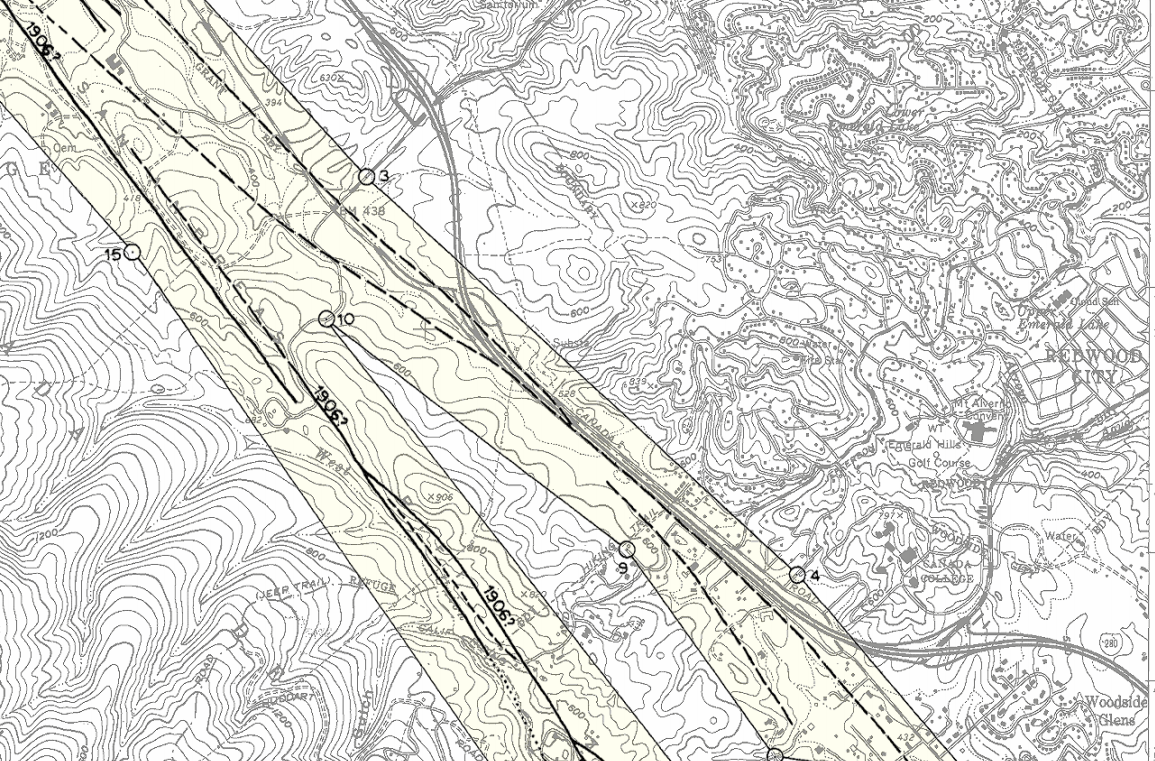

AAG Reason #3 Earthquakes. Below I’ve posted a zoomed in view of the “Woodside Quadrangle” area just west of Palo Alto and Redwood City. The shaded area (light yellow) illustrates the location of the San Andreas Fault where major earthquakes have been known to occur from time to time. Remember the big one in 1906? See the highway running just east of the fault line? That’s I-280.

There are other natural hazards that pose a threat to the same area, including tsunamis, making it a fairly crummy idea to build high density housing developments directly west of I-280 but I’m starting to feel like I’ve made my point. Plus all this geography is probably blowing up the graphing calculators that are typically so helpful in computing demand elasticity. Perhaps we should return to economics so we’re on a level playing field.

AAG Reason #4 Prices on the San Francisco Peninsula won’t go down just because supply goes up. This one must just torture economists who continue to stare at their 2-D graph showing how demand always goes down when supply goes up. There are loads of factors that drive real estate prices. Sure supply is one factor. Here are a few others: proximity to employment opportunities, good schools, high-quality entertainment and other cultural amenities. Turns out the San Francisco Peninsula might be one of the best places to live in the entire world if your primary goal is to find a high-paying job near great Thai food restaurants and outdoor live music venues. People also like to live in places with great weather and they like a view of the ocean or the mountains or a lake or a park with trees and flowers. You know, the commodity you refer to as “open space”. Yes, people definitely like open space. Kids like to run around and play. Adults like to walk dogs. In fact, a regular dose of nature is good for our physical and mental health. The ability to conveniently access this type of open space is good for quality of life and when you provide a high quality of life this funny thing happens: people want to live in the vicinity and, voilà, housing demand and real estate prices go up.

Don’t you find it a bit ironic that the most liberal cities, both globally and in North America, also offer the highest quality of life? Have you considered the possibility that quality of life drives real estate prices and what you refer to as liberal policy tends to foster higher quality lifestyles than the more conservative alternatives? If you disagree you should high tail it out of the Bay Area and move swiftly toward a more properly governed region with solid conservative principles. You know, a place where you can build anywhere and everywhere, a nice city like Houston. Wouldn’t you prefer great sprawling residential developments with unbearable traffic and commute times combined with little to no public transportation. Isn’t it great watching your life tick by while sitting in traffic and breathing oil-enriched air? But, hey, cheap real estate makes all the difference. Give Rice University a call. I’m sure they’d be delighted to bring you on board. Be sure to locate out past Katy where you’ll find inexpensive real estate and only a 90 minute one-way commute.

So, Dr. Sowell, if you want to talk about how liberals are bad for the economy perhaps you should focus on a topic within your wheelhouse. Maybe you can show how bloated government programs lead to higher taxes and limit economic growth. I’m probably with you on that one…so long as you include military spending. But, if you want to talk about location decisions, throw out your supply and demand charts. Instead, get yourself a good map or, better yet, a good geographer so you can learn more about these thorny spatial variables you and your geographically illiterate colleagues typically refer to as externalities.

14 Comments

A very eloquent way to telling someone they’re a moron. Well said, well said indeed.

Thanks, Bill! 🙂

Hi Justin

Thanks for this really intelligent article. In Australia, we used to start the planning process with Land Capability and Land Suitability mapping. The department responsible for that was shut down in the 80s. These days we seem to build nearly anywhere,engineer our way around the worst constraints, and insure against the balance. Wildfire areas seem to be managed via personal and community fire plans. Agreed though. You can’t engineer your way around earthquake and landslip prone areas.

Geographers have a real role to play in bringing broad-based common-sense to economic assertions such as the one you’re writing about. Do you think the profession is playing it?

Ian

Hi Ian, thanks for the comment! No, I don’t think professional geographers are playing their role. Part of the blame is a general disregard for the discipline. The other part of the blame, in my opinion, is due to the idiotic publishing circus driving academic promotion and tenure. Lots of good geography being done and then buried in obscurity. We need more geographers focusing on salient contemporary problems and making their ideas more accessible to the public. Thanks again! Best, Justin

I will keep this advice in mind as I start my Ph.D. geography program. I am so going to share this post with my brother, a Silicon Valley physicist who lives on that fragile ridge west of 280 near Ben Lomand. It will help in his work with the homeowners’ association there!

Thanks Sally! Let me know if he’s able to put it to some productive use. Best wishes, Justin

The cost of “protecting people from the inevitable wildfire activity is far too high” for what? If it’s subsidized by the government then let the market determine if the mystery “too high” is real, or a figment of your imagination. If it is subsidized, how much are the costs that are distributed to the rest of the state? If not, then what is it too high for? It’s clearly not for the million or so people that live there. I know Colorado is sparsely populated, so if the wildfires pose that much of a danger you’re probably seeing the government subsidize the rates below what the market would allow. But who knows because your analysis doesn’t go into any of that. Just a vague “far too high.”

So what if Sowell’s prime area is mountainous? Builders and engineers figured out how to build in mountains thousands of years ago. You admit there are already homes there so what is your point? That it costs more to build on a mountain? That’s not exactly original, but to be sure, it doesn’t cost an additional million and a half dollars to build 1200 square feet of dilapidated crap.

There was a big earthquake 110 years ago? Do you think insurance companies don’t factor that into their policies? They also factor tsunamis, hurricanes, tornadoes and all sorts of natural disasters into their rates. Let those projections determine the price to live there and we’ll see if it’s worth it or if it’s beyond your magical threshold of “far too high.” You display no recognition that risks apply to death, wealth, quality of life and numerous other things. Yet you’re sure you know which risks are too great. Your risk of dying in an automobile accident is greater than your risk of dying in an earthquake in a house built in the area Sowell mentions. That’s something we can test empirically and reach a definitive answer because, as you said, there’s already housing there. But of course your answer will be “someday,” or “it might,” or any of a host of words that can be twisted to fit a particular worldview with no actual relation to reality.

I’d much prefer the virtually non-existent decline in housing prices in Houston to the “fall off a cliff” free-fall that happened in San Fran during the crash. And the traffic is an example of bad government policy-roads where the costs are not distributed by use- as opposed to the “strong conservative principles” nonsense that exists in your imagination. If that’s an example of the grasp of basic economics employed by most geographers, then maybe Dr. Sowell will send you a copy of a basic economics text. That said, I’d like to see your data on traffic congestion, because San Francisco is consistently ranked as one of the most congested cities with the longest commutes in America. The last one I saw had it 2nd behind Los Angeles. According to the US Census Bureau(note to geologists: that’s an agency that keeps track of population, kinds of people, income, commutes, and all sorts of other things so if someone decides to compare cities they’ll have an inkling of what they’re referring to), San Francisco had a mean commute to work time that was longer than Houston’s. Congrats!

Reason # 4 might be the most economically illiterate paragraph ever written. There are numerous examples of places with great demand that don’t have San Francisco’s ridiculous prices. Houston, for starters. The fasting growing suburban area in the history of the world(so much for “unbearable” traffic) over a 20 year period with no housing bubble. Without government constraints, supply will quickly meet demand. You know the example you just used where people want to live next to great places to work and outdoor music venues and other things that you prefer and think are cool? Well that same demand creates demand for construction workers and developers and builders. Funny how they like to live where people are moving, huh?

Enjoy your artificially inflated housing value. Oh wait, they’re dropping off a cliff as we speak, once again. Of course you can blame it on Silicon Valley’s boom and bust cycle, while ignoring the same price declines in cities-with similar housing policies- thousands of miles from the Valley. Oh well, enjoy the view.

Here you go, dip shit: http://fortune.com/2015/09/15/cost-california-wildfires/

Here’s a summary of the costs for 2020: Roughly $1 billion annually is now being spent in California for fire suppression efforts.

Insurers shelled out $13B in 2020: Insurers shelled out $13B

[…] his newest column on the topic he continues his geographically illiterate approach to solving the affordable housing problem in the San Francisco Ba…. It amazes me how economists cling to naive neoclassical theories when they so quickly fall apart […]

Great writing, Justin.

I would add one thing. The experiment has already been done 400 miles to the south. Unrestricted growth policies in LA have created lots more really really expensive housing.

Clarke

Thanks, Clarke! And great point re LA!

http://onforb.es/1IxUmgV

Who can write more clearly than you about

such things! I assure you, nobody, I’ve seen something like this only on https://eastrivergreenway.org/how-to-write-definition-essay/. I enjoyed

the article and assume you have more such stuff? If so, so please post it since it is

somewhat unusual for me in the present moment, and not only

for me, that is my view. Hopefully, I can find an in-depth guide of yours and be aware of

all of the news and the latest data.